History and Background

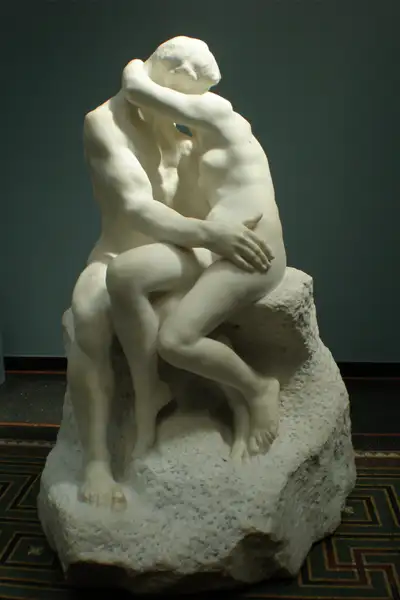

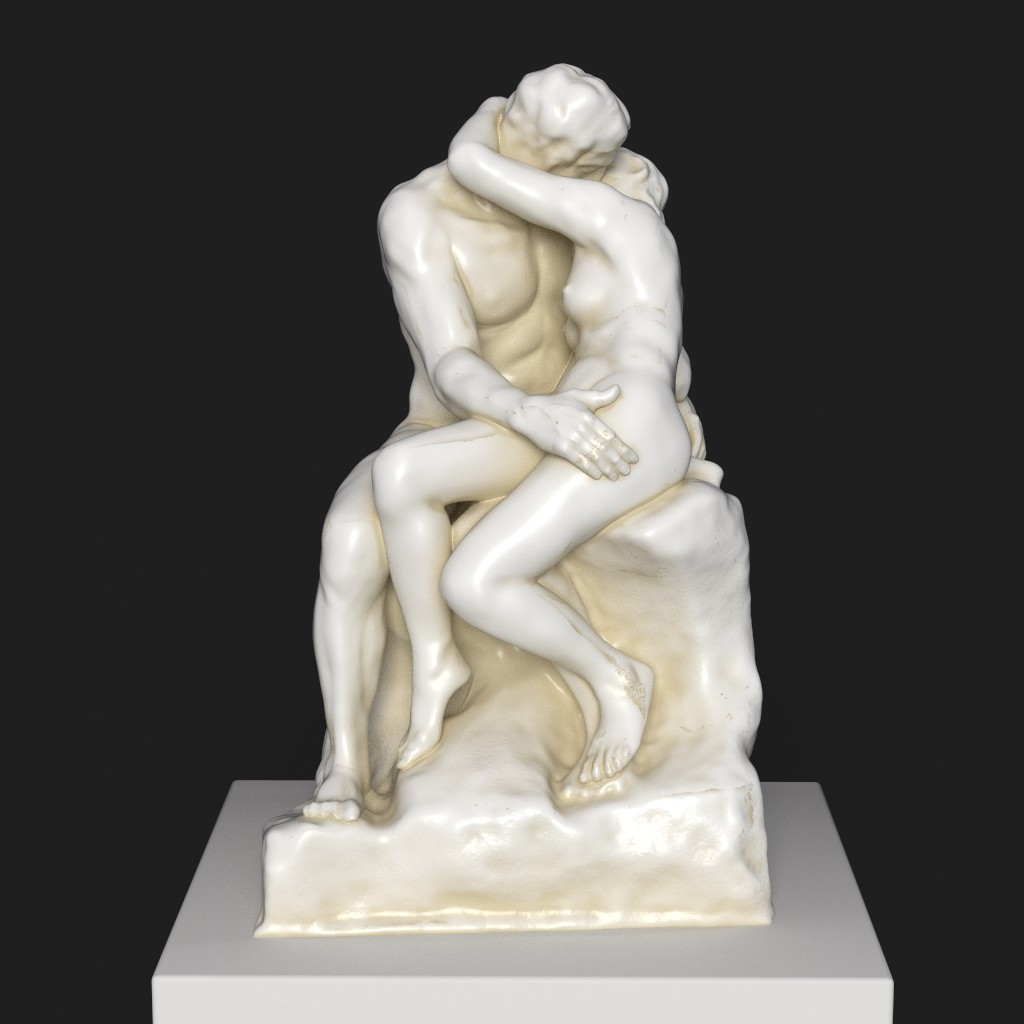

Auguste Rodin’s The Kiss (Le Baiser) was conceived in the early 1880s as part of his ambitious project The Gates of Hell. The sculpture originally portrayed Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini, tragic lovers from Dante’s Inferno. In Rodin’s initial design, the embracing couple appeared on the lower left of The Gates, representing a rare moment of passion in an otherwise hellish scene. By 1886, however, Rodin felt that this “depiction of happiness and sensuality” clashed with the tragic tone of The Gates, so he removed the couple and developed it into an independent work. He first exhibited the plaster model of The Kiss in 1887, where it “made an instant success” with critics and the public. Lacking any specific attributes to Dante’s characters (aside from a book in the man’s hand), viewers themselves coined the title The Kiss, recognizing the sculpture’s universal theme of love.

Encouraged by the positive reception, Rodin was commissioned by the French government in 1888 to produce a full-scale marble version for public display. Rodin took nearly a decade to complete this marble, delivering it in 1898. He jokingly referred to it as his “huge knick-knack”, aware that its “charming theme” made it widely appealing. When The Kiss was finally unveiled at the Paris Salon in 1898, it drew large crowds and widespread acclaim. Its sensual subject matter, however, also stirred controversy in more conservative circles. A bronze cast sent to the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago was deemed “unsuitable for general display” and placed in a private chamber accessible only on request. Similarly, when an enlarged copy of The Kiss was displayed in a small English town during World War I, local prudish citizens insisted it be draped with a sheet to avoid inciting “the ardour” of soldiers billeted nearby. These early moralistic reactions only heightened the sculpture’s notoriety and allure in the public imagination.

Over time, The Kiss evolved from a belle-époque sensation into one of the world’s most famous sculptures. Rodin himself authorized multiple versions to meet demand. By 1900, he had accepted commissions for two more large marble copies – one for an English collector, Edward Perry Warren, and another for the Danish brewer Carl Jacobsen. In addition, Rodin granted the Barbedienne foundry rights to produce limited-edition bronzes; hundreds of bronze casts were made in the following decades to satisfy collectors and museums worldwide. What began as a controversial depiction of illicit love thus entered the mainstream of art, with copies of The Kiss traveling internationally and enthralling new audiences. By the mid-20th century, The Kiss was firmly canonized as a masterpiece – for example, London’s Tate Gallery proudly acquired the Warren marble for the British nation in 1955.

Artistic Significance

Within Rodin’s body of work, The Kiss represents the artist’s exploration of human passion and emotional expression at its peak. Unlike many of Rodin’s other famous sculptures which feature solitary, tormented figures (The Thinker brooding alone, or anguished souls on The Gates of Hell), The Kiss celebrates the joyful union of two people. The entwined lovers radiate a sensual vitality – their bodies twist together in a fluid, dynamic composition that was quite daring for its time. Rodin’s mastery of anatomy and movement is evident in how naturally the figures merge; the viewer can sense the warmth and softness of the flesh carved from hard stone. This focus on intimacy and emotion marked a departure from the cold idealism of neoclassical sculpture that preceded Rodin. In fact, The Kiss harks back to the Romantic spirit, yet Rodin renders it with a modern, psychological realism that would influence 20th-century sculpture

Importantly, Rodin did not intend The Kiss to be merely titillating. He saw it as an homage to the power of love and to womanhood. “My sculptural women are full partners in ardor,” Rodin suggested – the female in The Kiss actively returns the embrace, rather than passively submitting. This egalitarian portrayal of passion (and the frank eroticism of the nude forms) scandalized some 19th-century viewers, but it also heralded a new honesty in art. In the history of sculpture, The Kiss is significant as a work that closed the 19th century on a note of uninhibited realism, paving the way for modernists to further break academic taboos. Ironically, Rodin himself had mixed feelings about the sculpture’s popularity. He noted that a kissing couple was a familiar subject in academic art – “a theme frequently treated… a subject complete in itself and artificially isolated”, he said, calling The Kiss“a big ornament… which focuses attention on the two personages instead of opening up wide horizons to daydreams”. In other words, Rodin recognized that The Kiss lacked the deeper symbolic complexity of some of his other works (such as his brooding monument Balzac). Nevertheless, its immediate emotional appeal and technical beauty have given it a unique place in Rodin’s oeuvre as a crowd-pleasing masterpiece that still bears the imprint of his genius.

Technical Aspects: Materials and Methods

Rodin’s The Kiss is most widely known in its marble version: a life-size sculpture measuring roughly 181×112×117 cm (about 72×44×46 inches). Carved from a single block of fine Carrara marble, the piece weighs over 5,500 pounds (2,500 kg). Achieving such a complex group in marble was a formidable technical challenge. Rodin employed a team of skilled assistants (called praticiens) to help translate his original clay models into stone. His usual process was to model the composition at a smaller scale in clay or plaster, then have assistants use pointing machines to chisel a larger copy in marble, closely following the model’s proportions. The Kiss was no exception. The first marble was chiefly roughed out by a studio sculptor named Jean Turcan, under Rodin’s watch, though Turcan departed before polishing was finished. Some art historians note that parts of the original marble remained “rough and unfinished”, possibly due to Turcan’s exit. Indeed, one hallmark of The Kiss is Rodin’s textural contrast: the lovers’ bodies are smoothly polished to a gleaming white, while the base on which they sit is left as rough-hewn rock. This juxtaposition of refined and raw surfaces heightens the sculpture’s sensual impact – the silky skin stands out against the coarse stone, symbolizing passion emerging from unworked nature.

Although marble was the prestige medium for the large versions, The Kiss also exists in other materials. Before carving the full scale piece, Rodin made numerous maquettes and studies in plaster and terracotta, and he authorized reductions in bronze as well. The Barbedienne foundry alone produced 319 bronze casts of various sizes

en.wikipedia.org, making The Kiss one of the most replicated sculptures of its era. These bronzes, often patinated in warm brown or greenish tones, allowed Rodin’s work to reach a wide audience and were more durable for outdoor display. (Interestingly, despite its design as a public monument, The Kiss was not displayed outdoors in Rodin’s lifetime; a bronze cast was finally installed in the Tuileries Garden in Paris in 1998.) Whether in marble or bronze, Rodin ensured quality by personally supervising his assistants’ work and applying the final touches himself. The finished piece is meant to be appreciated in the round: Rodin designed the composition with no single frontal view – the interlocking figures invite the viewer to walk around and observe the delicate details and shifting profiles from every angle. The technical brilliance of The Kiss lies in how the sculpture balances on the rock base (the figures almost seem to grow from it) and how natural the anatomy appears despite being carved from an unyielding block. Rodin’s deep understanding of form and volume allows the lovers to convey softness and movement, making The Kiss a tour-de-force of marble carving technique married to expressive storytelling.

Interpretations and Meaning

From its inception, The Kiss carried layered meanings. In Rodin’s mind it was tied to literature – specifically, the tale of Francesca and Paolo, whose forbidden love in 13th-century Italy was immortalized by Dante. In Dante’s Inferno, the couple is punished in Hell for committing adultery after reading the story of Lancelot and Guinevere. Rodin chose to depict the moment of their first kiss, a passionate instant just before tragedy: in the sculpture, Paolo still holds the book that drew them together. Notably, the lovers’ lips do not actually touch – an artistic decision that speaks volumes. This tiny gap between them creates a sense of suspended anticipation, as if time has paused at the apex of their passion. Some interpret this detail as a reference to the literary story: the couple’s bliss was interrupted by Francesca’s enraged husband, so the incomplete kiss foreshadows their fate. Others see it as Rodin’s way of heightening erotic tension – a kiss eternally about to happen, charged with potential energy. In either case, the sculpture captures love in a fleeting, fragile state, which adds emotional depth to the otherwise serene embrace.

Over the years, The Kiss has invited diverse interpretations. Many viewers simply perceive it as a universal symbol of love and desire, transcending its literary origin. With no obvious Dante reference in the figures themselves, one can enjoy the work as an ode to human affection in general. Indeed, Rodin’s contemporaries quickly attached a more abstract significance to it, preferring the title The Kiss for its broad, poetic resonance. Yet, beneath the romance, there is an undercurrent of ambiguity. As scholar William Schweiker observes, Rodin “reworks the tragic love of Francesca and Paolo”, transforming a “hellish kiss into a moving tribute to pure love”. The question remains: Is their love pure or profane? Innocent or immoral?. This moral tension – passionate love that is also adulterous – gives the piece a dramatic complexity. In a broader sense, Rodin’s sculpture plays with the dual nature of the kiss itself: an act that can signal both spiritual union and carnal sin.

From a modern perspective, The Kiss can also be viewed through a psychological or gender-based lens. Rodin was revolutionary in portraying the female figure as an active erotic participant; the woman in The Kiss wraps her arm around her lover’s neck and rises on her toes, indicating her equal yearning. This was a marked contrast to earlier Victorian norms, which idealized women as passive or chaste. As such, The Kiss can be seen as a celebration of women’s sexuality and mutual pleasure. At the same time, some critics have noted the idealization in the work – the two figures are youthful, beautiful, and eternally locked in an unconsummated moment. Rodin himself acknowledged that the sculpture was somewhat conventional in its “academic” treatment of love. Thus, interpretations of The Kiss often oscillate between praising its sensual realism and critiquing it as a kind of too-perfect reverie of love. The sculpture’s enduring power is that it supports both views: it is at once a heartfelt depiction of romantic passion and a carefully crafted artistic construct that invites us to ponder what a kiss truly represents.

Sculpture of The Kiss

Experience the timeless allure of “The Kiss,” a stunning replica of the iconic sculpture that captures a moment of profound intimacy and passion between two lovers. Crafted from high-quality resin and exquisitely painted with a marble and bronze patina, this piece embodies the elegance of classical artistry while ensuring durability for modern decor.

Inspir…

Comparisons to Other Works

Within Rodin’s Oeuvre: The Kiss can be illuminatingly contrasted with Rodin’s other famous creations, especially The Thinker and The Gates of Hell. The Thinker (1880) was originally conceived as a solitary figure atop The Gates, often interpreted as Dante contemplating the fates below. Where The Thinker embodies intellectual and spiritual struggle – a lone man lost in intense thought – The Kiss embodies physical love and emotional surrender. The two works are like yin and yang: one is introspective and static, the other extroverted and dynamic. Visually, The Thinker’s musculature and rough texture (in many bronze casts) convey tension and resilience, while The Kiss’s smooth interlocking forms convey softness and harmony. Both pieces became iconic in their own right, beyond the context of The Gates of Hell, showing the range of Rodin’s artistic vision. The Gates of Hell itself (a massive bronze portal Rodin worked on for decades) provides the origin story for both The Kiss and The Thinker. If we examine the final version of The Gates (now displayed in the Musée Rodin), The Kiss is conspicuously absent – Rodin deliberately removed this joyous couple, replacing them with more tragic figures to maintain the work’s somber narrative. In their original positions on the door, the lovers would have stood opposite the gaunt, starving Ugolino, another Dantean character who represents despair. This planned juxtaposition suggests Rodin’s nuanced understanding of Hell: even amidst torment, there could be a corner for love’s beauty. Ultimately, by extracting The Kiss and enlarging it, Rodin allowed the piece to stand alone as a celebration of passion, separate from the doom of The Gates. Meanwhile, The Thinker remained part of The Gates but also took on independent life in numerous enlargements. Together, these works illustrate Rodin’s ability to capture the spectrum of human experience – from the philosophical solitude of The Thinker to the sensual union of The Kiss – all originating from the same grand project.

Similar Sculptures by Other Artists: The universal theme of The Kiss has been explored by many artists, inviting comparison to Rodin’s approach. Perhaps the most striking foil to Rodin’s Kiss is Constantin Brancusi’s sculpture The Kiss (1907–08). Brancusi, who briefly worked as an assistant in Rodin’s studio, took a radically different path. His Kiss is carved directly by hand in limestone, featuring two block-like figures fused in a tight embrace. Where Rodin’s lovers are naturalistic and anatomically detailed, Brancusi’s are highly abstracted – their bodies are “nearly indistinguishable”, merging into a single cubic form with just a hint of arms and hair. Brancusi believed in “direct carving” and “intimate connection with the material”, rejecting Rodin’s use of assistants and polished realism. The difference is philosophical: Rodin expresses the feeling of love, fleshing it out in lifelike detail, whereas Brancusi expresses the idea of love, reducing two souls to an elemental unity. Brancusi’s The Kiss has an earthbound, primitive power – the two faces join into one shared profile, symbolizing total union. This modernist simplification was a direct challenge to Rodin’s legacy. As one critic put it, in Rodin’s Kiss, “the artist expressed the feeling of love, while Brancusi expressed the idea of love”. Despite their differences, both sculptures are milestones: Rodin’s Kiss marked the climax of 19th-century figurative passion in art, and Brancusi’s Kiss opened the door for 20th-century abstraction and the direct carving movement.

Rodin’s Kiss can also be compared to earlier interpretations of lovers in art. For instance, Antonio Canova’s Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1787) is a renowned marble group that, like Rodin’s work, captures a moment of tender contact. Canova’s neoclassical style, however, is polished to ideal perfection – Cupid and Psyche appear as serene, flawless beings, and the kiss (actually depicted mid-air, just before touching) is rendered with chaste elegance. Rodin, on the other hand, imbued The Kiss with a more earthy passion; his lovers are nude and unidealized, and their emotional intensity is palpable rather than mythic. This shift from Canova’s gentle classicism to Rodin’s sensual realism reflects the changing artistic values of the 19th century, as artists moved toward more genuine human emotions. In turn, Rodin’s portrayal of a passionate kiss paved the way for even bolder works by 20th-century artists. Aside from Brancusi, we see echoes of The Kiss in the oeuvre of Rodin’s own protégée, Camille Claudel. Her sculpture The Waltz (1889–1905), for example, shows a couple entwined in a dance, nude and in love, arguably influenced by Rodin’s frank depictions of intimacy. While Claudel’s figures are more elongated and swirling, the shared theme of rapturous embrace highlights Rodin’s impact on contemporaries. In summary, The Kiss stands at a crossroads: looking back, it resonates with classical and romantic depictions of loving couples; looking forward, it anticipated modernist and expressionist interpretations of the theme. Its enduring fame often makes it the benchmark against which other “kissing” sculptures are measured – whether the sumptuous gold-leaf painting The Kiss by Gustav Klimt (1908) or Robert Indiana’s pop art sculpture LOVE (which spells out the word but implies a kiss), Rodin’s influence echoes wherever art seeks to capture the essence of a kiss.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

Since its creation, The Kiss has crossed cultural boundaries, becoming one of the most recognizable images in Western art. In the early 20th century, news of Rodin’s daring sculpture spread internationally, often stirring debate about art and morality. The piece challenged prudish attitudes in Victorian-era societies – its censorship at the Chicago Exposition and in Edwardian England only fueled public curiosity. Over time, however, The Kiss came to be celebrated rather than shunned. In France, it was quickly embraced as a national treasure (the French state proudly displayed the original marble in the Musée du Luxembourg for years. Elsewhere, as copies proliferated, people of different cultures could encounter Rodin’s message of love firsthand. By the mid-20th century, The Kiss had been exhibited across Europe, the Americas, and beyond, eliciting admiration from diverse audiences who might never read Dante but instantly grasp the sculpture’s emotional language.

The influence of The Kiss on other artists is evident both directly and indirectly. Directly, Rodin’s willingness to depict erotic love with such honesty helped liberate artists to explore sensual themes. Sculptors like Maillol and Klimt (in sculpture and painting respectively) would further celebrate the nude couple as subject matter in the early 1900s. Indirectly, even artists who reacted against Rodin’s style were responding to the path he forged. Constantin Brancusi’s turn to abstraction (discussed above) was partly a response to the expressive naturalism epitomized by The Kiss. Many modern sculptors cite Rodin as the father of modern sculpture, crediting him with breaking academic rules – for example, Henry Moore admired Rodin’s innovative treatments of form and often studied Rodin’s work for inspiration on how sculpture interacts with space. In a broader cultural sense, The Kiss has transcended art circles to become a pop culture icon. It has appeared in films, literature, and even songs. (One curious tidbit: the British progressive rock band Yes was inspired by Rodin’s The Kiss for their song “Turn of the Century” in 1977) The sculpture has been referenced in television – notably, an episode of All in the Family features a comical dispute over a replica of The Kiss, highlighting generational differences in attitudes toward nude art. Even Monty Python satirized it in an animation, attesting to its firm place in the public consciousness.

Perhaps most telling of The Kiss’s cultural impact is how contemporary artists continue to engage with it. In 2003, British artist Cornelia Parker created an installation by wrapping Rodin’s The Kiss (then on display at Tate Britain) in a mile of string. This act was a provocative commentary referencing Marcel Duchamp’s famous string installation, and it temporarily obscured Rodin’s sculpture from view. The public reaction was heated – many found the string intervention “offensive to the original artwork”, and one protester even cut the strings while couples symbolically kissed around the shrouded statue. Such events prove that The Kiss still evokes strong feelings and dialogue about the role of art and intimacy. More than 130 years after it was first unveiled, Rodin’s The Kiss remains a touchstone of love in art – a work that people continue to celebrate, interpret, reinvent, and even physically interact with in acts of homage or rebellion. Its image is instantly recognized across cultures as an embodiment of romantic love, making it a true cultural icon beyond its art-historical importance.

Preservation and Exhibitions

Today, Rodin’s The Kiss can be admired in several major museums and public sites around the world. The original large marble – the one commissioned by the French state – has been housed in Paris since its creation. It entered the national collection in 1901 and now resides in the Musée Rodin, Paris, where it is a centerpiece of the collection. This marble is lovingly cared for, kept indoors to preserve its delicate surfaces. In the sculpture’s long history, it has occasionally traveled for exhibitions; notably, in 1995 the Musée d’Orsay in Paris brought together all three of Rodin’s full-size marble versions of The Kiss for a special exhibit – a rare reunion of these monumental lovers. The second marble version, made for Edward P. Warren, eventually found a home at the Tate Gallery in London. After a colorful journey (including years hidden in an English stable and a stint on loan in a town hall), the Warren marble was purchased by the Tate in 1955. It is now typically displayed at Tate Modern in London, where British audiences continue to be drawn to its timeless portrayal of passion. The third marble copy, commissioned by Carl Jacobsen, has been part of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen since 1906. Danish visitors thus have their own share of Rodin’s masterpiece, exhibited in a beautiful classical museum setting.

Aside from these marble centerpieces, a posthumous marble copy of The Kiss (carved in 1929 by sculptor Henri Gréber under the Rodin Museum’s authorization) is on display at the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia. This copy, virtually indistinguishable from Rodin’s lifetime carvings, signifies the sculpture’s reach to American shores. Furthermore, countless bronze casts of The Kiss populate museum collections globally. According to records, Rodin’s contracted foundries produced several hundred bronzes in various sizes. By French law, only the first 12 casts are considered “originals,” but even later casts have historical and artistic value. Notable bronzes can be seen at the Musée Rodin (outdoor garden), the Musée d’Orsay, the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff (which acquired a cast in 1912), the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, the Museo Soumaya in Mexico City, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., among others. In Buenos Aires, a plaster cast is on display at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, showing the piece in its original studio material form. This wide distribution means that art lovers on multiple continents can experience The Kiss firsthand.

In terms of preservation, the marble versions require the most care – marble is sensitive to acid, moisture, and physical contact. Museums keep the statues under controlled light and climate, and touching is strictly prohibited (oils from human hands can damage the marble). Regular inspections ensure no micro-cracks or surface issues develop. The bronzes, being more robust, have even been placed outdoors: for instance, the life-size bronze in the Tuileries Garden in Paris lets the public encounter Rodin’s lovers in the open air, year-round. This outdoor display, finally realized at the end of the 20th century, fulfills Rodin’s vision of The Kiss as a work that could grace public spaces and inspire passersby with its beauty. Indeed, whether ensconced in a museum or under the sky, The Kiss continues to be exhibited to maximum effect. Special exhibitions still feature the sculpture – for example, Rodin centennial shows, or themed exhibitions about love in art – demonstrating that The Kiss remains a star attraction. Its cultural journey from a studio in Paris to the halls of museums worldwide, and even to city plazas and gardens, underscores the sculpture’s universal appeal and the diligent efforts to preserve it for future generations. Sculpture enthusiasts and general visitors alike find that seeing The Kiss in person is a moving experience – a chance to connect with Rodin’s masterpiece across time and culture, and to witness the tender humanity he carved in stone so long ago.