This ancient marble group (over 2 meters tall) has awed viewers for centuries with its dramatic depiction of agony. It portrays the Trojan priest Laocoön and his two young sons entwined by giant serpents, a scene of mythical tragedy carved in stone. Since its rediscovery in 1506, this sculpture has been celebrated as one of antiquity’s greatest works. In this article, we explore the stylistic, historical, and cultural significance of Laocoön and His Sons, its journey from ancient Rome to Renaissance fame, and its profound impact on the history of art.

Mythological Background and Subject

In classical mythology, Laocoön was a priest in the city of Troy who warned his compatriots against bringing the Greeks’ wooden horse inside the city walls. In Virgil’s Aeneid, Laocoön utters the famous line Timeō Danaōs et dōna ferentēs, translated as “I fear the Greeks, even bearing gifts.” This is the origin of the adage “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts,” a warning against trusting a seemingly benevolent enemy. The gods favoring the Greek cause—accounts vary between Poseidon or Athena—punished Laocoön for his warning by sending two colossal sea serpents. The serpents rose from the sea and attacked Laocoön and his sons during a sacrificial ceremony, strangling them in their coils and silencing his plea.

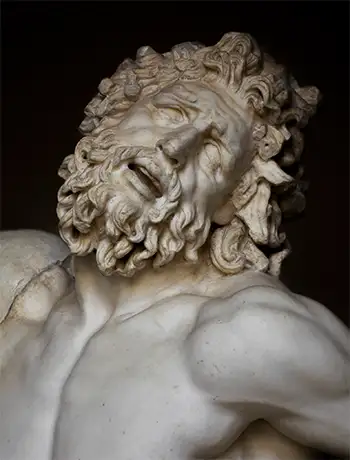

The sculpture captures this intense moment of divine punishment. Laocoön is shown at the center, muscular and struggling, his body contorted as he fights the snakes that encircle his torso and legs. His sons, one to his side and one at his feet, also grapple in vain with the serpents. The youngest boy on Laocoön’s left appears near defeat, whereas the older son on the right twists away in terror. Every face tells a story of agony and desperation: Laocoön’s head is thrown back, mouth open in a cry of pain, his brow knotted in a tortured expression. His children’s faces mirror fear and suffering. This vivid tableau brings to life a lesser-known episode of the Trojan War saga, turning a moment of myth into a powerful human drama.

Style and Composition: Hellenistic Drama in Marble

The Laocoön group is renowned as a pinnacle of the Hellenistic “Baroque” style in ancient Greek art. Carved in the 1st century BCE (or possibly early 1st century CE), it exhibits the trademarks of Hellenistic art: dynamic movement, extreme emotion, and intricate detail. The composition is complex and pyramidal, designed to be seen in the round. Laocoön’s body forms a strong diagonal “X” shape, with limbs flung out—one arm raised over his head (now restored) and one leg extended. The serpent coils connect the three figures, creating a unified tangle of bodies and snakes. This open, twisting design leads the eye around the sculpture, conveying frantic motion as the attack unfolds.

A striking aspect of the style is the portrayal of human agony with raw intensity. The sculpture has been called “the prototypical icon of human agony” in Western art. Unlike suffering saints in later Christian art (whose pain might be portrayed as noble or redemptive), Laocoön’s torment has no higher purpose or reward – it is pure physical and emotional anguish. His face, especially as seen in close-up, shows veins bulging and brows furrowed in an almost unbearable pain. Yet, the artists balanced this realism with classical restraint: Laocoön’s beauty and noble form remain evident even in distress. His mouth is open, but (notably) not in a grotesque scream. Art historians since the 18th century have remarked on this. The German scholar Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, in his 1766 treatise Laocoön, famously asked why the sculptors did not depict Laocoön screaming, concluding that a face distorted by an outright scream would appear ugly in sculpture and betray the era’s aesthetic of measured beauty. Thus, the statue achieves a poignant balance—depicting excruciating pain while preserving a sense of dignity and classical pathos. This quality led the pioneering art historian Johann J. Winckelmann to praise the Laocoön as an embodiment of “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur,” even in the throes of suffering.

The technical craftsmanship is equally impressive. The group was hewn from fine marble, with undercutting so deep that parts of the snakes and limbs are fully separated from the mass, creating dramatic shadows. (Pliny the Elder, ancient Rome’s famous natural historian, marveled that it was carved “out of a single block of marble”, though modern analysis shows it is composed of several pieces fitted together.) Musculature and anatomy are rendered with keen attention: Laocoön’s ribcage strains under his skin, and the tension of tendons in the figures’ limbs is visible. Such realism makes the viewer almost feel the victims’ struggle. Originally, like most Greek statues, it was likely painted in lifelike colors, which would have heightened its visual impact even more.

Ancient Origins and Historical Context

Who created this tour-de-force of sculpture? The earliest reference comes from Pliny the Elder in the 1st century AD. Pliny saw the statue in the palace of Emperor Titus in Rome and praised it as superior to all paintings and bronzes. He attributed it to three sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydoros. This attribution suggests the piece was a product of the Hellenistic Greek world, even if it was found in Rome. Scholars debate whether the Vatican marble is the original Hellenistic creation or a later Roman copy made during the early Imperial era. In either case, it was certainly crafted for a Greco-Roman patron of high status, possibly a member of the imperial family. Stylistically, it shows kinship with the art of the Pergamene school (2nd century BC), which also excelled in dramatic, emotional sculpture. Many believe the Laocoön group may be a Roman-era reproduction of a Pergamene-style bronze masterpiece. If so, the original might date to around 200 BC, whereas the marble version is often dated somewhere between 50 BC and 70 AD.

Culturally, the subject of Laocoön would have resonated with Roman audiences familiar with the Trojan legend (the Romans traced their mythic origins to Trojan survivors). A sculpture depicting Troy’s tragic priest would blend Hellenistic artistry with a story that flattered Roman heritage via Virgil’s epic. Displayed in an imperial palace, the Laocoön was likely meant to impress viewers with both its virtuosic artistry and its poignant message about fate and the gods’ wrath. For ancient Romans, it was a showpiece of paideia (cultural knowledge) and an exemplar of the heights art could achieve. Little could they imagine that it would one day lie buried for a millennium – only to astound the world anew during the Renaissance.

Rediscovery in the Renaissance (1506)

The Laocoön and His Sons remained hidden for centuries after antiquity, until a dramatic rediscovery in the early 16th century. In February 1506, workers digging in a vineyard on Rome’s Esquiline Hill (near the ruins of Emperor Nero’s Golden House) stumbled upon large marble fragments of a sculpted group. Recognizing that something extraordinary had been found, the site owner alerted authorities. Pope Julius II, an avid patron of the arts and antiquities, dispatched his court experts to investigate. Among them was none other than Michelangelo Buonarroti, the famed sculptor of the Pietà and painter of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, who hurried to the scene alongside the architect Giuliano da Sangallo.

As the earth was cleared, the statues emerged: Laocoön and his sons, astonishingly preserved minus a few missing pieces. According to a later account by Francesco da Sangallo (Giuliano’s son, who was present as a boy), upon seeing the unearthed figures his father immediately exclaimed, “That is the Laocoön, which Pliny mentions!”. The identification was instant, thanks to the fame of Pliny’s description. Artists on-site were reportedly so awed that they began making sketches on the spot.

Julius II moved swiftly to acquire the masterpiece. By March 1506, he had purchased the sculpture (rewarding the finder with a pension and a job). The pope then installed Laocoön in the Vatican, in a special niche in the Vatican Palace’s Belvedere Courtyard. This was effectively the first artwork of what would become the Vatican Museums – indeed the Vatican regards this event as the foundation of its art collection. Crowds of artists, scholars, and dignitaries came to marvel at the ancient marvel. Its impact was immediate and immense. The discovery of such a powerful Hellenistic sculpture in the heart of Rome “was a turning point in the course of Renaissance art” and even “planted the seeds for the emergence of the Baroque movement” in art.

For Renaissance artists, the Laocoön embodied the long-lost perfection of antiquity. They studied its anatomy and emotional expressiveness closely. Michelangelo, in particular, was deeply influenced by the Laocoön’s complex poses and musculature. The sculpture’s example of how the human figure could convey intense emotion and dynamic motion helped inform Michelangelo’s own works. In the figures of his Rebellious Slave and Dying Slave (sculpted c. 1513 for Julius II’s tomb), one can see echoes of Laocoön’s twisted torso and straining muscles. Michelangelo’s painted nude figures (ignudi) on the Sistine Chapel ceiling likewise reflect the influence of the Laocoön, especially in their athletic poses and expressive tension. As a testament to the statue’s impact, Michelangelo is said to have described the Laocoön group as a “miracle of art”.

Other contemporary artists were equally captivated. The young Raphael incorporated a homage to Laocoön: in his fresco The Parnassus (1511) he gave the poet Homer the face of Laocoön, effectively linking epic suffering with artistic genius. Engravings and drawings of the Laocoön circulated widely through Europe, spreading its fame. In fact, so many reproductions were made that some artists even satirized it. A notable example is a 16th-century print (attributed to Niccolò Boldrini after Titian) that parodied the group by depicting the struggling figures as apes – a cheeky commentary on how ubiquitous and emblematic the statue had become.

Sculpture of The Laocoön Group at The Vatican Museums Vatican City

Immerse yourself in the grandeur of Hellenistic art with our exquisite replica of The Laocoön Group, a monumental masterpiece originally housed in the Vatican Museums. Crafted with meticulous attention to detail, this stunning sculpture captures the intense emotion of the Trojan priest Laocoon and his sons, as they confront the terrifying serpents sent by the g…

The Restoration Saga: Missing Arms and Modern Discoveries

When it was unearthed, the Laocoön group was largely intact but several key parts were missing: Laocoön’s right arm, the right arm of one son, part of the other son’s hand, and some sections of the serpents. The sculpture’s drama was evident even in this incomplete state, but the question of how to restore it quickly arose. Julius II’s architect Donato Bramante reportedly organized an informal competition around 1510, inviting top sculptors to propose how the missing pieces should be reconstructed. Michelangelo, who had carefully studied the statue, believed Laocoön’s right arm was originally bent back over his shoulder in a contorted pose, intensifying the strain. Others thought the arm should be extended outward in a heroic, outstretched gesture. According to Giorgio Vasari, the proposals were judged by Raphael, and a young sculptor Jacopo Sansovino won the contest with an outstretched arm design.

For a time, the statue remained displayed without any additions. But in 1532, Pope Leo X commissioned Giovanni Antonio Montorsoli, a pupil of Michelangelo, to restore the group. Montorsoli attached a new right arm to Laocoön – choosing to make it straight and extended, pointing upward – as well as restorations to the missing son’s arm. This restored version, with Laocoön’s arm flung high, became the accepted vision and was copied in casts and drawings for centuries. It wasn’t until the 20th century that this view was dramatically revised.

Fast-forward to 1906: an archaeologist named Ludwig Pollak discovered a curious marble arm fragment in a Roman builder’s yard, not far from the find spot of the Laocoön. The broken piece showed a flexed, muscular arm with a tense hand – it looked very much like it could belong to the missing Laocoön. Pollak gave the fragment to the Vatican Museums, where it languished in storage for decades. Only in 1957 did the museum officially study the piece and conclude that it was indeed Laocoön’s original right arm. This arm was bent at the elbow, drawn back over the shoulder, exactly as Michelangelo had theorized. The Vatican promptly removed the old extended arm and attached the newly identified original arm to the statue, restoring the pose the ancient artists had intended. After 400+ years, Michelangelo’s intuition was vindicated – Laocoön now raises a crooked arm behind his head in a gesture of desperate resistance, not a triumphant outstretch. Modern conservation in the 1980s further stabilized the ensemble, and today the statue is presented as close to its ancient state as possible (the sons’ arms remain restored but more discreetly).

The saga of Laocoön’s arm is often recounted as a fascinating footnote in art history, illustrating how our understanding of antiquity can change with new finds. It’s remarkable that a work so famed since the Renaissance was still awaiting the reattachment of an original limb in the mid-20th century. The restoration history also highlights how Renaissance and Baroque-era tastes (preferring a bold, outstretched arm) differed from ancient composition, which favored a tighter, more anguished pose. Today, visitors in the Vatican Museums see Laocoön much as Pliny saw it – a father’s last futile struggle, arm bent back as he succumbs to tragedy.

Impact and Legacy in Art History

Few artworks can match Laocoön and His Sons in terms of lasting influence. From the moment of its rediscovery, it has shaped artistic imagination and theory. In the Renaissance, as we saw, it was a touchstone for masters like Michelangelo and Raphael. The sculpture’s sinuous forms and emotive power directly inspired Michelangelo’s works for Pope Julius II, and through him left its mark on the course of Western art. It also influenced the teaching of art; Renaissance and Baroque art academies often used casts of Laocoön as models for studying anatomy and composition. Young artists learned to sketch the group from all angles, considering it a supreme example of how to convey action and passion in sculpture.

During the Baroque period (17th century), the influence of Laocoön only grew. Baroque artists were drawn to dramatic, spiraling compositions and intense emotion—all qualities epitomized by the ancient statue. The great Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens, for instance, was enthralled by Laocoön. During his stay in Rome he made over fifteen detailed drawings of the sculpture, studying the muscular anatomy and complex groupings, and these studies informed the dynamic figures in his own paintings. More generally, the theatricality seen in Baroque art—sweeping gestures, strong diagonals, and faces twisted in emotion—“owe a lot to Laocoön and his sons”. One can see echoes of Laocoön’s pose in countless Baroque works, from Bernini’s writhing sculptures to the emotive saints in the paintings of Caravaggio’s followers. The Laocoön provided a classical precedent for portraying extreme human emotion, something Baroque artists eagerly embraced (even as they typically gave their figures religious context or redemptive meaning, which Laocoön lacks).

Even beyond the visual arts, Laocoön sparked intellectual debate. In the 18th century it became central to discussions about aesthetics. The German art historian Winckelmann saw in Laocoön the ideal of Greek art’s beauty even in pain, while Lessing took the statue as the starting point for his famous essay Laocoön (1766), which contrasts how pain and violent action are depicted in art versus poetry. Lessing argued that the sculptors moderated Laocoön’s agony (no wild scream, no unbearable gore) because visual art should capture a pregnant moment of beauty and suffering combined, whereas a poet like Virgil could describe the scene in more gruesome detail over time. This debate greatly influenced modern understanding of the limits and strengths of each art form. In short, a single statue from antiquity became the cornerstone for entire theories of art and literature, underlining its unique importance.

The sculpture’s journey through history also saw it become a coveted prize in political realms. In 1798, when Napoleon Bonaparte’s forces invaded Italy, the Laocoön was seized as part of France’s war booty. Along with other masterpieces, it was carted off to Paris, where it went on display in the Louvre (then called the Musée Napoléon). The French considered it a jewel of the classical world that had come into their possession. Only after Napoleon’s defeat was Laocoön returned to the Vatican in 1816. This episode attests that by the 18th–19th century, Laocoön was not just an artwork but a symbol of cultural heritage, aggressively sought after by empires. Its safe return to Rome was a celebrated event, and it resumed its place as a must-see icon for Grand Tour travelers and art students.

The tortured expression of the Trojan priest, carved with exquisite realism, has fascinated viewers and scholars. The statue’s depiction of raw pain (without heroic consolation) was unprecedented, earning it descriptions like “a miracle of art” by Michelangelo and “the prototypical icon of human agony” by modern commentators. This expressive power influenced artists from the Renaissance through the Romantic era, and even today the Laocoön continues to captivate the public at the Vatican Museums.

Over the years, the sculpture has also provoked intrigue and speculation. One modern controversy emerged in 2005, when art historian Lynn Catterson proposed that the Laocoön might not be ancient at all but rather a brilliant forgery by Michelangelo. She pointed to a sketch by Michelangelo that resembles Laocoön’s torso and to records of unexplained payments to the artist shortly before 1506, suggesting he could have sculpted the group and planted it to fool the pope. However, most experts dismiss this theory; the consensus remains that Laocoön is an authentic classical sculpture. If nothing else, the forgery debate shows how the statue’s fame makes it a magnet for imaginative theories.

Conclusion

Laocoön and His Sons stands not only as a marvel of ancient art but as a bridge between epochs. Its discovery at the dawn of the 1500s injected the emotive power of Hellenistic art directly into the Renaissance, forever shaping the trajectory of Western sculpture and painting. Artists for centuries have studied its every contour — the knotted muscles, the anguished faces, the serpentine composition — drawing inspiration for their own masterpieces. Culturally, it has kept alive the tragic tale of Laocoön, reminding generation after generation of the old lesson to “beware of Greeks bearing gifts,” and of the capricious nature of fate and gods in human affairs. From Pliny’s praise in ancient Rome to Napoleon’s appropriation, from Winckelmann’s and Lessing’s essays to modern museumgoers’ gasps, Laocoön has never lost its grip on the human imagination.

Today, as you stand before this sculpture in the Vatican’s Octagonal Court, you witness the very same spectacle that so astonished observers in antiquity and the Renaissance. The marble group seems almost alive, locked in an eternal struggle that transcends time. Laocoön and His Sons invites us to reflect on the universal themes of suffering, courage, and the poignant beauty of the human form under duress. Over two thousand years after it was carved, it remains a compelling testament to the expressive potential of art – truly, in the words of Michelangelo, a miracle of art that continues to speak to us across the ages.