Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475–1564), known simply as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet who stands as one of the towering figures of the High Renaissance. Celebrated in his own lifetime as “Il Divino” (the divine one) for his artistic genius, Michelangelo is regarded as one of the greatest artists in history. While he excelled in multiple fields, he always considered himself primarily a sculptor. His marble masterpieces like the Pietà and David – both completed before he turned 30 – and later works such as Moses are among the most famous sculptures ever created. This article provides an in-depth look at Michelangelo’s life and training, examines his sculptural techniques and philosophy, explores his influences and historical context, and analyzes his most important sculptures. It also discusses his artistic legacy and enduring impact on later generations of sculptors.

Early Life and Training

Michelangelo was born on March 6, 1475 in Caprese, a small town in the Republic of Florence. He was born into a family of minor Florentine nobility that had lost its wealth, and his father briefly served as a local administrator. From a young age, Michelangelo showed artistic talent and a passion for drawing, but pursuing art was seen as a lower-status vocation. At 13 he became an apprentice to the prominent Florentine painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, despite his father’s initial objections. He spent only a year in Ghirlandaio’s workshop – according to his early biographer Condivi, Michelangelo felt he had little more to learn there. His true interest was sculpture. Around 1489, the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo de’ Medici, took the exceptionally talented young artist under his patronage. Michelangelo was invited to live and study at the Medici palace, where he was immersed in an environment of humanist scholars, poets, and artists. More importantly, he had access to the Medici’s renowned sculpture garden, which was filled with fragments of ancient Roman statuary. Under the guidance of Bertoldo di Giovanni – a pupil of Donatello and curator of Lorenzo’s antiquities – Michelangelo studied classical sculptures and learned to carve in marble. During these teenage years he sculpted his first pieces, notably the “Madonna of the Stairs” (a low relief) and “Battle of the Centaurs” (a marble relief c.1492). The latter work, with its writhing classical nude figures, foreshadowed Michelangelo’s lifelong fascination with the male form and dynamic composition. This early immersion in the art of antiquity and the Florentine Renaissance laid the foundation for Michelangelo’s style, blending classical ideals of beauty with a bold realism and emotional intensity.

In 1494, Florence was plunged into political turmoil – the Medici were expelled and the reformer Savonarola took power. Michelangelo, then 19, left the unstable city in search of work. He traveled to Bologna, where he was hired to carve several small figures for the grand tomb of St. Dominic. Even in these early commissions in Bologna (1494–95), Michelangelo’s distinctive approach shone through. Departing from the ornate style of the previous sculptor, he gave his figures a new gravity and “compactness of form” inspired by Classical antiquity and the solid realism of earlier Florentine art. By 1496, Michelangelo’s reputation reached Rome, and at age 21 he was invited there by a powerful banker. This move would kick-start the young sculptor’s meteoric rise to fame.

Early Career and Rise to Fame: Rome and Florence

In Rome, Michelangelo’s talent attracted the attention of influential patrons. One of his first major sculptures was “Bacchus” (1496–1497), a life-size marble of the Roman wine god commissioned for a garden. Bacchus was daringly unorthodox: the drunken god is depicted with a swaying pose and rolling eyes, about to stumble. The figure’s “conscious instability” – an almost off-balance stance – cleverly evokes the effects of inebriation. Inspired by ancient Roman nude statues, Michelangelo made the Bacchus fully three-dimensional and viewable from all sides, a sculpture in the round meant to be appreciated from multiple angles. Though later somewhat overlooked, Bacchus demonstrated Michelangelo’s virtuosity with marble and his willingness to push boundaries of composition and realism.

Michelangelo’s first true masterpiece came at age 24, with his “Pietà”. Completed in 1499 for the French Cardinal Jean de Bilhères, this marble group was made as an altarpiece for the cardinal’s chapel in Old St. Peter’s Basilica. The Pietà depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Christ after the Crucifixion – a traditional subject in Northern European art, but relatively novel in Italy. Michelangelo’s interpretation of the scene was unprecedented in its beauty and balance. He carved the two figures ingeniously from a single block of Carrara marble, composing them in a pyramidal structure that gives the sculpture stability and grace. Mary’s face is serenely young and exudes dignity, while the lifeless Christ is rendered with astonishing anatomical realism – every muscle, vein, and fold of skin appearing soft and natural. Michelangelo deliberately contrasted the vertical, draped figure of the Virgin with the horizontal, nude body of Christ, highlighting the dual themes of life and death, maternal grief and divine sacrifice. The polished surface and delicate details (such as Christ’s wound and the fabric textures) testify to Michelangelo’s technical perfectionism. When unveiled, the Pietà caused a sensation; no one had seen such a poignant and lifelike portrayal of this sacred moment. Amazingly, it is the only work Michelangelo ever signed – he carved his name across Mary’s ribbon-like sash after hearing observers attribute the work to another sculptor. The Pietà made Michelangelo famous virtually overnight and established him as one of the leading sculptors of his time.

Michelangelo returned to Florence as a rising star in 1501. There, he took on a project that would define the Florentine Republic’s identity and his own legacy: the carving of “David.” The city’s authorities commissioned a colossal statue of the biblical hero David, intended originally to crown a buttress of Florence Cathedral. Michelangelo was given an enormous block of marble that had been quarried decades prior and left unfinished by another sculptor. Accepting the challenge, he carved the David between 1501 and 1504. The result was a masterpiece of such scale and quality that it “has continued to serve as the prime statement of the Renaissance ideal of perfect humanity”. Standing 5.17 meters tall, Michelangelo’s David was the first colossal nude statue of the High Renaissance – the likes of which had not been created since Classical antiquity. Sculpted in gleaming white marble, David is depicted not after his victory over Goliath (as earlier artists showed), but before the battle – alert and tense, a moment of poised potential. Every detail demonstrates Michelangelo’s knowledge of anatomy and his skill in conveying psychological intensity: the furrowed brow, the veins bulging in the hand holding the sling, the subtle twist of the torso in contrapposto stance. Despite its massive size, the sculpture’s proportions and idealized beauty evoke the perfection of ancient Greek sculpture, while its expression and detail embody the Renaissance celebration of human dignity

When the David was completed, its quality was so outstanding that a committee of Florentine officials and artists (including Leonardo da Vinci) decided it deserved a more prominent placement than the cathedral roof. In 1504, the statue was installed in front of the Palazzo Vecchio (City Hall) as a proud symbol of the Florentine Republic’s defiance of tyrants. The choice of David – the underdog who defeated a giant with God’s favor – resonated with Florentines as a metaphor for their small republic standing up to powerful rival states and internal Medici plotting. Michelangelo’s David thus embodied not only artistic idealism but also the political spirit of its time. It remains one of the most acclaimed sculptures in the world, admired for its breathtaking craftsmanship and the intense, contemplative expression on David’s face that seems alive with thought.

The Middle Years: Papal Service and Late Florentine Works

The fame Michelangelo garnered from David led to high-profile commissions from the Pope in Rome. In 1505, Pope Julius II summoned Michelangelo to design an ambitious tomb for him. The project – which would occupy Michelangelo on and off for 40 years – proved both a grand challenge and a personal frustration. Julius’s initial tomb plan was colossal, calling for over 40 statues and multiple levels. Michelangelo began feverishly, even traveling to Carrara to quarry massive blocks of marble. However, the Pope’s priorities shifted and the tomb was put on hold repeatedly (in part because Julius instead tasked Michelangelo with painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling in 1508, against the sculptor’s own preferences). The stop-and-start project of Julius II’s tomb was only finally completed in 1545, on a greatly reduced scale. Nonetheless, it yielded some of Michelangelo’s finest sculptural achievements, most notably the figure of Moses.

Carved around 1513–1515, “Moses” was intended as a centerpiece for the tomb’s second tier. The sculpture depicts the Old Testament prophet seated, holding the Tablets of the Law. Michelangelo portrayed Moses with a powerful build and intense expression, as if he has just descended from Mount Sinai. A notable feature is the pair of horns on Moses’ head – a detail derived from the Latin Vulgate translation of Exodus, in which Moses is described as having a radiant (horned) face after speaking with God. This horned Moses had precedents in medieval art, but Michelangelo’s rendition is by far the most famous. The Moses exudes a palpable terribilità, a term contemporaries used to describe the awe-inspiring, formidable quality in Michelangelo’s art. His facial expression and bulging arm veins convey suppressed energy and righteous anger (some interpret the figure as momentarily restraining himself upon seeing the Israelites’ idolatry). The technical carving is extraordinary – Michelangelo rendered Moses’ long, curling beard with such delicacy that Vasari marveled “the hairs… are so soft that it seems the iron chisel must have become a brush”. Every detail of the muscles, drapery, and even Moses’ tablets is carved with a mix of realism and idealization, bringing the marble to life. Moses sits in a contrapposto twist, one leg drawn back, giving the static pose latent motion. This sculpture alone confirmed Michelangelo’s supremacy among sculptors of his day – Vasari wrote that Michelangelo finished the Moses “unequaled by any modern or ancient work”. Even in reduced form, Julius’s tomb (installed in San Pietro in Vincoli church, Rome) became famous largely because of the commanding presence of Moses, flanked by Michelangelo’s smaller sculptures of Rachel and Leah (allegories of the contemplative and active life) completed by his assistants.

During the same period in Florence (between 1515 and 1534), Michelangelo undertook another major sculptural project – the Medici Chapel (New Sacristy) in the Basilica of San Lorenzo. Commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici (later Pope Clement VII), this funerary chapel was meant to honor two younger Medici dukes who died in 1516 and 1519. Michelangelo designed the architecture and the sculptural program, creating a unique fusion of architecture and sculpture. The two tombs he built inside feature some of his most original creations: reclining allegorical figures representing times of day. On one tomb (for Giuliano de’ Medici) sit Night and Day; on the opposite tomb (for Lorenzo de’ Medici) are Dawn and Dusk. These marble figures (carved in the 1520s) are imbued with complex meaning and virtuoso artistry. Night, for instance, is a female nude shown in a twisting pose, eyes closed in sleep, while Day is a male figure, muscular and awakening with a turn of the head. According to Michelangelo, these personifications symbolized the unceasing passage of time leading inevitably to death. The poses and proportions of the figures are intentionally unusual – elongated or over-muscular in parts – reflecting a move toward Mannerism and Michelangelo’s willingness to distort forms for expressive effect. Contemporary admirers were astonished by the lifelike detail (legend says Night looked so real that a viewer remarked she must be alive, to which Michelangelo quipped that she was simply sleeping). The Medici Chapel sculptures, though not fully completed when Michelangelo left Florence for good in 1534, stand as a testament to his inventive genius in later years – merging architectural setting and sculpture into an immersive artistic statement.

Michelangelo’s final decades were spent in Rome, where he focused increasingly on architecture (becoming Chief Architect of St. Peter’s Basilica) and painting (The Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel, 1536–41), but he never abandoned sculpture. In his 70s, he carved the poignant “Florentine Pietà” (c.1547–1555, also called the Bandini Pietà) intended for his own tomb – a group of Jesus being taken down from the cross, supported by Mary, Mary Magdalene, and Nicodemus (a self-portrait of Michelangelo). Frustrated with a flaw in the marble, Michelangelo partially broke and abandoned this statue. Remarkably, in the very last years of his life, approaching age 89, he began another Pietà. This final sculpture, the “Rondanini Pietà,” was worked on until the last days of his life in 1564 and left unfinished. It portrays a spectral, elongated Virgin Mary clasping the body of Christ, both figures seemingly dissolving into rough marble. Though Michelangelo did not fully carve it, the Rondanini Pietà offers a moving glimpse into the artist’s spiritual and artistic mindset at the end: the once supremely confident master reducing forms to their essence, perhaps seeking redemption through his art. Michelangelo died in 1564, having outlived the High Renaissance and seen younger Mannerist artists take art in new directions under the shadow of his immense influence.

Michelangelo’s Sculptural Techniques and Artistic Philosophy

Michelangelo approached sculpture with a combination of technical mastery and a deeply personal artistic philosophy. He worked primarily in Carrara marble, believing it to be the noblest material for sculpture. His process was famously intense and hands-on – unlike some contemporaries, Michelangelo preferred to do all the carving himself rather than rely on assistants for rough-hewing. He had an extraordinary ability to envision the finished statue within a block of marble before he began. As he famously declared, “the sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material”. In other words, Michelangelo felt his task was to liberate the figure imprisoned in the stone. Indeed, he said he “saw the angel in the marble and carved until [he] set him free.” This reflects a Neo-Platonic philosophy he absorbed in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s circle: the idea that the ideal form lies hidden within matter, and the artist brings it forth.

Carving Technique: Michelangelo’s carving technique was bold and often without elaborate preparatory models. Though he did make small clay or wax models on occasion, he was known for sometimes carving directly into the marble with minimal outlines, an almost improvisational approach that awed contemporaries. He employed the traditional tools of marble carving – including the point chisel (subbia) for rough blocking, the toothed gradina chisel for refining forms, and finer flat chisels and rasps for detail and polish. However, the way he used these tools was distinctive. Examination of Michelangelo’s unfinished works (like the Captive or Slave figures) reveals his process: he would fully finish one part of a statue while other parts remained raw block, a method contrary to the usual practice of evenly working down the whole figure. For example, he might complete a head or a hand in exquisite detail on one face of the marble, while the back of the block still showed chisel groves where forms were barely roughed out. Michelangelo did this to “see and finish a part in order to find more hidden in the block,” effectively using the finished section as a guide to proportion the rest. This process created the dramatic effect in pieces like the Awakening Slave where the figure appears to emerge out of rough stone. It also required supreme confidence and foresight – a mistake in a finished section could ruin the piece, since you cannot add marble back once removed. Michelangelo’s non-finito (unfinished) works, such as the four Captives (Slaves) intended for Julius II’s tomb, seem to intentionally showcase this “freedom of the figure” from its marble prison: limbs and torsos appear to be fighting to free themselves from the uncarved stone. This effect may be partly intentional, partly a result of abandoning the sculptures, but later critics have admired them as art in their own right.

Another aspect of Michelangelo’s technique was his anatomical expertise. He famously studied human anatomy by dissecting cadavers as a young man in Florence, which gave him an intimate understanding of muscles and bones. He could portray the human body with scientific accuracy when he wanted, but he also took liberties, enlarging or exaggerating forms for expressive impact. For instance, his David’s head and hands are slightly oversized for a standing figure – likely deliberately, to ensure that the power and thought of the hero are emphasized (and that these parts would appear in correct proportion when the statue was originally intended to be viewed from below). Michelangelo was a master of the human form and believed it to be the ultimate vehicle for conveying spiritual and emotional truth in art. This belief sometimes led him to depart from strict realism in favor of what he considered a more spiritually true representation (as seen in the graceful but unnaturally elongated neck of the Night figure, or the immense torso of his Day figure).

Michelangelo’s artistic philosophy placed sculpture above all other art forms. In Renaissance theory, disegno (drawing/design) was the foundation of the arts, and Michelangelo’s sculptures and paintings alike demonstrate powerful design through the poses and gestures of figures. But he argued that sculpture, which shares three-dimensional space with the viewer, was superior to painting, which is an illusion on a flat surface. He disparaged the additive process of building up a form in clay (saying that adding material was akin to painting), insisting that true sculpture was subtractive, releasing form from matter. This near-spiritual undertaking – of finding the form within – meant the artist had to engage in a dialog with the stone. Michelangelo’s reverence for the human form, especially the male nude, was such that nearly all his sculptures, even religious subjects, have a physical intensity and often a restrained emotion that comes through pose and gesture rather than overt expression. This “sculptural” way of thinking also carried into his paintings, which often resemble painted sculpture in their muscular, volumetric figures.

Influences and Historical Context

Michelangelo developed his style at the height of the Italian Renaissance, drawing on many influences yet ultimately forging a path so original that he became a standard for others. In his formative years in Florence, he was surrounded by the legacy of Early Renaissance masters. The works of sculptors like Donatello undoubtedly informed Michelangelo’s youth – Donatello’s realistic approach and his sculptures of David and other figures set a precedent for portraying biblical heroes in humanist terms. Michelangelo’s David can be seen as a continuation (and enlargement) of that Florentine tradition, taking the idealized nude of antiquity and imbuing it with a new level of psychological depth. He also would have known the works of Andrea del Verrocchio (who sculpted a bronze David) and Jacopo della Quercia, whose expressive reliefs in Bologna some scholars see as an influence on the young Michelangelo when he visited that city in 1494–95.

The greatest classical influence came from ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. From his years in the Medici garden onward, Michelangelo studied and even copied classical sculptures. He absorbed the classical ideals of proportion, balance, and anatomical perfection – evident in works like David which consciously emulates the stance of ancient athletes. A famous event took place in 1506, when the ancient marble group Laocoön and His Sons was unearthed in Rome; Michelangelo was present at its discovery and was profoundly impressed by the dynamic composition of the writhing figures. The influence of Hellenistic pieces like the Laocoön and the fragmentary Belvedere Torso (which Michelangelo admired greatly) can be seen in his later works – for example, the twisting poses and emotional tension of the Medici Chapel figures and some Sistine Chapel figures owe much to those classical models.

Michelangelo’s contemporaries also shaped his art. He had a well-known rivalry with Leonardo da Vinci, who was about 23 years his senior. In 1504, both were involved in a project to paint large battle scenes in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio (neither finished). While the two geniuses had a fraught relationship, Michelangelo did learn from Leonardo’s innovations. Leonardo’s mastery of human anatomy, his subtle gradations of expression, and his use of complex poses influenced younger artists in Florence. Scholars note that Michelangelo’s works around 1500–1505, such as the Tondo Doni (his only panel painting) and the Bruges Madonna, show figures in twisting motion and interlocking composition that reflect Leonardo’s explorations. Michelangelo publicly downplayed any influence – he was famously proud and claimed to have no masters but nature – yet it’s clear he absorbed useful lessons. According to art historians, “Leonardo’s works were probably the most powerful and lasting outside influence to modify Michelangelo’s work,” especially in the early 1500s. Michelangelo managed to blend Leonardo’s dynamism with his own penchant for monumental strength, achieving a unique balance of motion and stability in his sculpture

The historical context of Michelangelo’s career was one of vibrant artistic patronage and shifting political fortunes. He came of age in Florence during its Renaissance golden age under Lorenzo de’ Medici, when classical humanism and arts flourished. He then worked in Rome at the height of Papal patronage. Popes like Julius II and Leo X (a Medici) were willing to invest lavishly in art to glorify the Church and their own legacies, providing Michelangelo with unprecedented opportunities (the Sistine Chapel ceiling, tombs, facades, etc.). However, the pressures of working under powerful patrons also meant Michelangelo had to navigate volatile situations – Julius II could be impatient and even quarrelsome with him, leading to legendary disputes (Michelangelo at one point fled Rome in anger over non-payment). The turbulent politics of Florence also intruded: in 1527, the Florentines expelled the Medici again and Michelangelo, a republican sympathizer, briefly took charge of fortifying the city against siege. After Florence fell in 1530, Michelangelo had to make peace with the returning Medici (hence completing the Medici Chapel under their rule). These events influenced his work’s tone – some have read the somber Night and Dusk as Michelangelo’s meditation on Florence’s lost liberty.

Religiously, Michelangelo lived during the High Renaissance followed by the Reformation era. He was deeply spiritual (especially in later life) and his works reflect a passionate faith, but also the era’s uncertainties. The Catholic Counter-Reformation was beginning in the 1540s, and Michelangelo’s later works like the Last Judgment were scrutinized by the Church for propriety (he faced minor criticism for the nudity in the Sistine frescoes, which were later partly censored). His last sculptures, the Pietà groups, have a private, introspective spirituality, perhaps influenced by the devout reformist Catholic climate of his old age.

In sum, Michelangelo synthesized the influences of classical art, the innovations of his peers, and the rich cultural milieu of Renaissance Italy to create a style entirely his own. His sculptures are products of their time – embodying Renaissance humanism’s reverence for antiquity and the human form – yet they also transcended their era, setting new benchmarks for artistic expression.

Major Sculptures and Their Analysis

Michelangelo produced numerous sculptures, but a few stand out as his most important and iconic works. Below, we examine several of these masterpieces in detail, including their background, artistic features, and impact.

David (1501–1504)

Michelangelo’s David is perhaps the most celebrated sculpture in the world – a masterpiece that symbolized the Renaissance ideal of man and the civic pride of Florence. As discussed earlier, the statue was commissioned by Florence’s cathedral authorities, who provided Michelangelo with a giant marble block that had been abandoned by others

britannica.com. The artist carved David over the course of about three years, unveiling it in 1504 to immediate acclaim.

Standing 17 feet tall, David depicts the biblical hero as a magnificently proportioned nude youth. Unlike earlier Renaissance statues of David, which showed him after victory (often with Goliath’s head at his feet), Michelangelo chose to represent David before the battle, in a moment of concentrated focus. The figure carries his sling over his shoulder, the stone in his right hand, but these attributes are understated – what commands attention is David’s intense gaze and poised stance. He stares into the distance, the furrows in his brow and tight lips conveying vigilance and courage. His body exhibits contrapposto balance: the weight is on the right leg, left leg relaxed, hips and shoulders counterbalance each other, giving a gentle S-curve to the torso. This classical stance, derived from ancient Greek sculptures, imparts both realism and dignity.

On a technical level, Michelangelo’s carving is superb. The anatomy is highly naturalistic – one can trace the musculature under the skin, from the strong thighs and finely carved abs to the sinews on David’s neck. Yet Michelangelo also idealized the body to an extent: David’s physique is that of an athletic adult rather than a youth who fought as a shepherd. The head and especially the right hand are slightly enlarged relative to the body. Far from a mistake, these exaggerations likely served to emphasize David’s intellectual and physical power (and perhaps were calculated to compensate for viewing angles when the statue would be raised high). The David embodies fortezza (fortitude) and ira (righteous anger) held in suspension – a perfect symbol for the city of Florence which prided itself on its republican vigilance. As mentioned, once completed, the statue was deemed too beautiful and significant to put on a roof. Instead it was installed in Piazza della Signoria, becoming a civic emblem. Florentines saw it as an allegory of their own situation: a small republic (David) facing larger foes and internal threats (the Medici or foreign monarchies). Indeed, David was positioned looking south-east, towards Rome, as if warning the Medici (exiled at that time) to stay away.

The impact of Michelangelo’s David was immediate and lasting. Artists of the time marveled at its combination of classical form and emotional expressiveness. For the next two centuries, David served as a model for the male nude in art – many subsequent sculptures and paintings drew on its pose and proportions. Michelangelo had demonstrated how a biblical subject could be rendered with the majesty of an ancient god, yet with the psychological presence of a real person. Today, David remains a cornerstone of Western art history, often regarded as the epitome of male beauty and heroic virtue in sculpture.

Sculpture of Michelangelo’s David

Immerse yourself in the timeless beauty of our exquisitely crafted resin replica of Donatello’s iconic “David.” Originally commissioned by the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore in 1408, this masterpiece embodies the artist’s inaugural foray into the world of sculpture. Our piece expertly captures the essence of the original, portraying the young biblical hero wit…

Pietà (1498–1499)

Michelangelo’s Vatican Pietà was the masterpiece that announced the arrival of a new sculptural genius at the dawn of the 16th century. Carved when he was only 23–24 years old, the Pietà established Michelangelo’s reputation and remains one of the most emotionally powerful sculptures ever created.

The term pietà refers to any depiction of Mary supporting the dead Christ, but Michelangelo’s rendition has become the iconic Pietà. Commissioned by French Cardinal Jean de Bilhères for his tomb chapel, the sculpture was intended to inspire devotion – and it does so by presenting an idealized vision of compassion and sacrifice. Michelangelo chose to show the Virgin Mary as youthful and serene, rather than middle-aged as she would have been at Christ’s death. This eternal youth symbolizes her purity and ageless beauty, aligning with Renaissance ideals (and perhaps inspired by Dante’s poetic description of Mary as both virgin and mother). Mary’s face is calm and reflective, not distorted by grief; her eyes are cast down on her son’s body in a melancholy gaze. In her lap lies the lifeless body of Jesus, smaller in scale relative to Mary to create a harmonious composition (and to emphasize her maternal embrace enveloping him). Christ is depicted with masterful realism – his limbs graceful even in death, head gently fallen back, and the marks of crucifixion (nail wounds) subtly visible. His sculpted flesh appears soft, with delicately carved details such as the veins in his arms.

Artistically, the Pietà is a showcase of balance and contrast. The figures form a pyramid, with Mary’s head at the apex and the drapery of her voluminous robes widening to the base. Michelangelo carved Mary’s robes with deep folds that both support Christ’s body and create an interplay of light and shadow. The voluminous drapery contrasts with the smooth, bare flesh of Christ, highlighting the sacred vs. mortal, the living (Mary) holding the dead. Michelangelo also contrasts Mary’s large, stable form with Christ’s smaller, limp body – yet the entire group reads as one cohesive unit, a single Pietà rather than two separate figures. This was a remarkable achievement in extracting two figures from one block and making them compositionally one. Observers often note the delicate way Mary cradles Jesus – one hand supports under his arm, the other lies open in a gesture of acceptance or sorrow, inviting the viewer to contemplate the sacrifice. The high polish Michelangelo gave the marble adds to the transcendent beauty; light flows across the surfaces, giving the figures a lifelike glow.

When unveiled in St. Peter’s in 1500, the Pietà was instantly recognized as a masterpiece of unprecedented finesse. Pilgrims and Romans alike were astonished at how a cold stone could be made to convey such warmth, tenderness, and tragedy. One observer at the time exclaimed that it was a miracle anyone could carve something so “divine.” Over the centuries the Pietà has elicited deep religious reverence and artistic admiration. It was moved into St. Peter’s Basilica proper and remains there, now protected behind glass after an unfortunate vandalism in 1972. For Michelangelo, this work was a triumph – it was “a key work of Italian Renaissance sculpture” that in many ways launched the High Renaissance in sculptureg. The fact that he signed it (along the sash across Mary’s chest) is often interpreted as a bold claim of authorship from a young artist who knew he had created something extraordinary. To this day, Michelangelo’s Pietà stands as an enduring image of grief and love, marrying Renaissance humanist beauty with profound Christian devotion.

Sculpture of Michelangelo’s Pieta in St Peters Basilica Vatican

Experience the timeless beauty of the Pietà, a masterful Renaissance sculpture by Michelangelo Buonarroti, now captured in exquisite detail in this stunning resin replica. Crafted with meticulous care, this piece embodies the profound emotion and artistry of the original, housed in St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City.

The Pietà, completed between 1498 and 1…

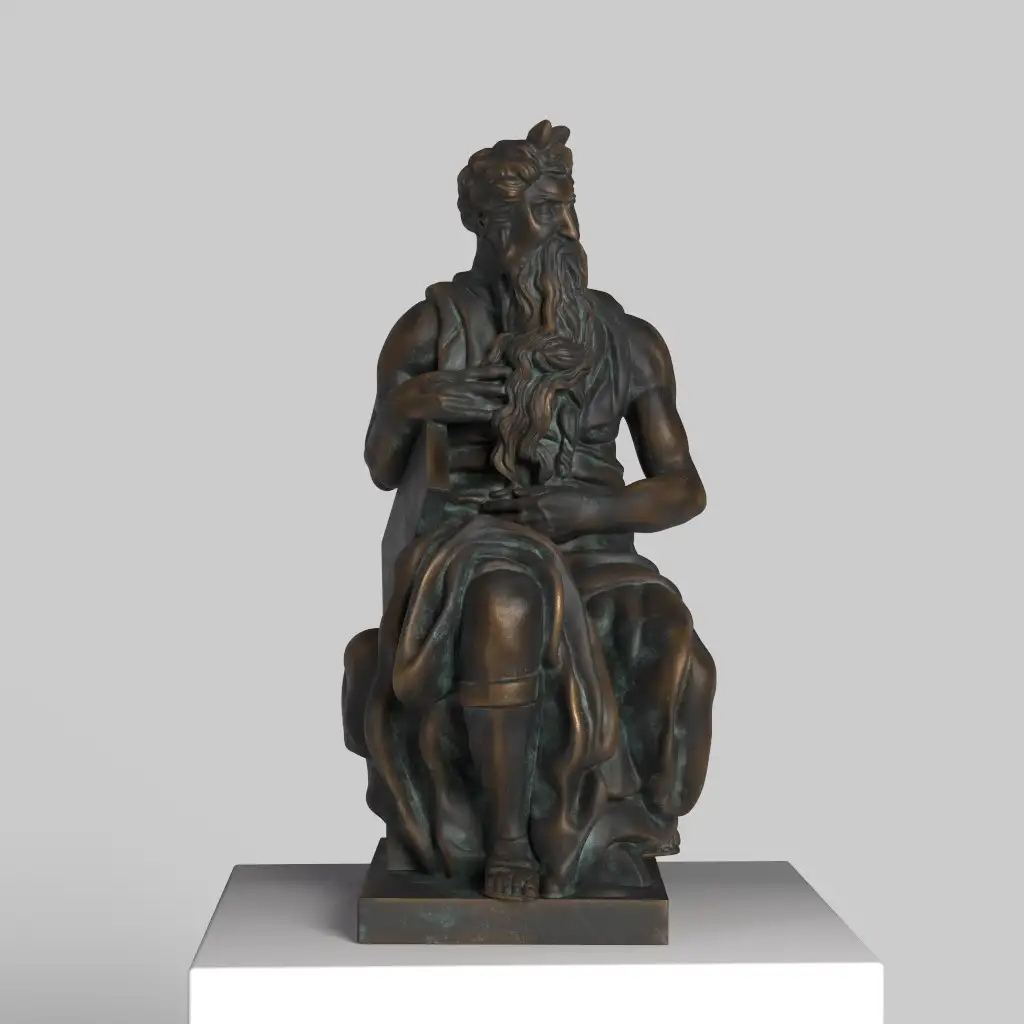

Moses (c.1513–1515; completed 1542)

Michelangelo’s Moses is the central figure of the tomb of Pope Julius II and a sculpture that Michelangelo himself reportedly regarded as among his finest creations. It represents Moses, the lawgiver of Israel, in a moment of grave contemplation and barely restrained energy. Commissioned as part of Julius II’s grand tomb, Moses was originally meant to sit on an elevated tier and be paired with an equivalent statue of St. Paul. In the final, scaled-down tomb, Moses sits at ground level in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, yet still dominates the space.

Moses is depicted seated, yet his pose and gaze impart a sense of movement and emotion. He is shown with his right arm protectively draped over the Tablets of the Ten Commandments, holding them against his side, and his left arm long and tense on his lap. His torso twists to his left as his head turns to the right, as if something has caught his attention. The most striking features are Moses’ facial expression and his flowing beard. Michelangelo carved Moses with a furrowed brow, intense eyes, and lips set in an expression of profound seriousness – he seems to be in righteous anger or on the verge of rising. This is often interpreted as the moment when Moses comes down from Mt. Sinai and beholds the Israelites worshipping the Golden Calf, inciting his fury. Indeed, Moses’ famous glare has been described as capable of turning stone to dust. The long beard cascading to his lap is carved with breathtaking skill: it’s so detailed and voluminous that it practically becomes a character of its own. Each curl is chiseled with precision, demonstrating Michelangelo’s ability to turn hard marble into what looks like soft, flowing hair.

One unusual detail is the horns on Moses’ head, small pointed protrusions on his forehead. This feature comes from a translation nuance – the Latin Vulgate described Moses’ face as “horned” (when it meant “radiant”) after communing with God. Medieval and Renaissance artists often depicted Moses with horns as a result. Michelangelo included them, likely aware of the tradition, and they add to Moses’ otherworldly, ancient authority. Far from looking absurd, the horns in Michelangelo’s handling appear like a natural extension of Moses’ prophetic aura.

The sculpture’s monumentality is enhanced by Michelangelo’s depiction of musculature and form. Moses is robust – his arms and legs are powerfully built, suggesting great strength held in repose. The veins on his forearms and the sinews of his hands are visible, conveying life and readiness to act. Even the simple drapery (a cloak wrapping around his waist and legs) is arranged in heavy folds that complement the composition and emphasize the mass of the figure. When viewing Moses in person, many find that the statue has a commanding, almost intimidating presence – the eyes seem to follow the viewer. There’s a famous legend that Michelangelo, upon finishing Moses, struck the statue on the knee and shouted “Perché non parli?!” (“Why don’t you speak?!”), so convinced was he that he had brought it to life.

Michelangelo’s Moses has influenced countless artists and fascinated viewers for centuries. It became a sort of prototype for depicting prophets and patriarchal figures in art – dignified, muscular, and emotionally intense. Sigmund Freud even wrote a famous analysis of Michelangelo’s Moses, pondering the psychological nuances of its expression. Whether or not one reads those depths, the technical and artistic mastery of Moses is undeniable. It exemplifies Michelangelo’s ability to instill a sculpture with a complex inner life, making marble seem alive with emotion and thought.

Sculpture of Moses

Introducing our exquisite replica of the iconic sculpture “Moses,” a masterful representation of the legendary figure revered across various Abrahamic faiths. This stunning piece captures the essence of Michelangelo’s monumental marble work, originally crafted for the tomb of Pope Julius II in the early 16th century. Our sculpture, meticulously handcrafted fro…

Other Notable Sculptures: Slaves, Madonnas, and Late Pietàs

In addition to the famous works above, Michelangelo created numerous other sculptures that are cornerstone pieces in the history of art. Among these are the so-called Slaves (or Captives), a series of figures originally intended for Pope Julius II’s tomb. Two finished examples, the “Dying Slave” and “Rebellious Slave,” carved in the 1513–1516 period, are now in the Louvre in Paris. They each depict a nude male figure of idealized beauty, caught in a moment of struggle. The Dying Slave stands with his head tilted back and eyes closed, one arm raised above his head and the other hand resting on his chest – his pose suggests a swoon or a trance, perhaps symbolizing the soul’s release from the body. The Rebellious Slave, by contrast, seems to wrestle against bonds, his head turned sharply and muscles tensed as if resisting captivity. These sculptures may have allegorical meanings (representing captive arts or provinces for Julius’ triumph, according to some theories), but they are most admired for their masterful form and the emotional resonance of the poses. Michelangelo’s handling of anatomy in the Slaves is superb – the Dying Slave’s relaxed torso and the Rebellious Slave’s straining limbs are textbook studies of how to represent the human body in different states of tension.

Notably, Michelangelo left four other slave statues in various stages of completion (the “Atlas,” “Awakening,” “Young,” and “Bearded” Captives, now in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence). These unfinished slaves are extraordinary because they allow us to see Michelangelo’s carving process – each figure looks half-entombed in marble, as if the men are struggling to free themselves from the rock. Michelangelo may have abandoned them when the tomb project was downsized, but they eloquently symbolize that idea so central to his sculpture: the soul (or form) imprisoned in matter, yearning for release. Artists and critics through the ages have found them profoundly poetic; Auguste Rodin, the great 19th-century sculptor, was notably influenced by the power of Michelangelo’s unfinished figures.

Michelangelo also sculpted a number of Madonnas and smaller works. The Madonna and Child was a recurrent subject – one beautiful example is the “Madonna of Bruges” (1504), a marble statue of the Virgin and Child that was purchased by merchants and installed in Bruges, Belgium. Unlike earlier static Madonnas, Michelangelo’s version shows Mary as a young mother in a moment of contemplation, as the Christ child stands between her knees about to step forward, a notably human and gentle interaction. Another early work, “Cupid”, which Michelangelo allegedly forged as an “ancient” statue to test a patron’s eye (according to legend), unfortunately does not survive, but the story indicates Michelangelo’s deep understanding of classical art even as a youth.

Finally, in his old age, Michelangelo returned to the theme of the Pietà that he had mastered in his youth. Around 1547 he began the Florentine Pietà, intended for his own tomb. This group shows Christ being lowered by Mary Magdalene and Nicodemus (with Mary the Mother supporting from below). Michelangelo, dissatisfied, mutilated parts of it; it remains a powerful but fractured piece, later repaired by an assistant. In 1550s, Michelangelo turned to drawing and poetry to express his devout meditations, but the sculptor’s urge was still in him. The Rondanini Pietà (so named for the palazzo where it long stood) was his final sculpture, worked on until the last days of his life in 1564.

The Rondanini Pietà is dramatically different in style from the Vatican Pietà carved 65 years earlier. Michelangelo began with a different composition (traces of a previous figure remain), then pared it down to a bare-bones vision: an emaciated Christ being supported by a thin, grieving Mary from behind. The forms are elongated and almost abstract – Christ’s legs are barely sketched out, and much of the surface is rough. Michelangelo seemed to strip away all ornament and even anatomy, seeking an expressive essence. The result is a sculpture that has an aura of deep sorrow and spiritual resignation. It’s as if Michelangelo was unmaking the marble, converging on pure emotion. This unfinished Pietà, completed by the hand of death rather than the artist, has fascinated modern viewers and is seen as a forerunner of expressionist and abstract tendencies in art. It provides a poignant bookend to Michelangelo’s sculptural career: from the polished youthful brilliance of the Pietà of 1499 to the raw, pensive mystery of the Pietà of 1564, the arc of Michelangelo’s art encapsulates the Renaissance’s full range – from classical harmony to intensely personal expression.

Artistic Legacy and Influence

Michelangelo’s impact on the art of sculpture – and Western art as a whole – cannot be overstated. In his lifetime, he was celebrated as “the greatest artist alive”, and indeed, even Renaissance contemporaries regarded his work as almost superhuman in skill and conceptual depth. Giorgio Vasari, in his 1550 Lives of the Artists, lauded Michelangelo as “supreme in not one art alone but in all three” (sculpture, painting, and architecture), essentially crowning him the paragon of Renaissance genius. Michelangelo’s sculptures became benchmarks of excellence that later artists aspired to match. The term “Michelangel(esque)” came to denote works inspired by his powerful musculature and dynamic poses. Many sculptors and painters of the Mannerist period (mid-16th century) tried to emulate his energetic compositions and anatomical exaggerations – often exaggerating them further. For example, sculptors like Baccio Bandinelli and Bartolomeo Ammannati produced muscular statues clearly in Michelangelo’s wake (though none achieved his finesse), and painters like Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino took inspiration from the twisting, complex poses of Michelangelo’s figures.

In the 17th century, the Baroque era, artists continued to be influenced by Michelangelo. Gian Lorenzo Bernini, perhaps the only sculptor who could challenge Michelangelo’s crown in the eyes of posterity, was a great admirer of the Renaissance master. Bernini’s early David (1620s) in some ways competes with Michelangelo’s by choosing a different moment (mid-action) but the very comparison underscores Michelangelo’s enduring influence. Bernini also absorbed Michelangelo’s ability to carve marble with astonishing realism – for instance, the flowing beard of Bernini’s Moses in the fountain of Piazza Navona surely nods to Michelangelo’s Moses. In painting, Peter Paul Rubens studied Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel figures and translated their Herculean anatomy into his own muscular saints and heroes, spreading Michelangelo’s influence across Europe.

Through the centuries, Michelangelo’s work was periodically re-evaluated but never ignored. The Neoclassicists of the 18th century, like Antonio Canova, revered David and the Medici tomb figures for their ideal beauty. In the 19th century, Auguste Rodin found inspiration in Michelangelo’s non-finito sculptures; Rodin’s Thinker owes something to the brooding pose of Lorenzo de’ Medici from the Medici Chapel, and his partial figures (torso fragments etc.) were arguably legitimized by Michelangelo’s unfinished Captives. Michelangelo’s notion that a figure could be left emerging from the stone influenced modernist sculptors’ appreciation for the raw material and process. Even Henry Moore in the 20th century cited Michelangelo’s prisoners as an influence on how he thought about the relationship between form and block.

Michelangelo’s legacy also includes the very image of the “artist” as a lofty, inspired creator. Prior to the Renaissance, sculptors were seen more as craftsmen. Michelangelo (and Leonardo) helped elevate the artist’s status to one of intellectual and creative genius. The fact that Michelangelo was the first Western artist to have a biography published in his lifetime speaks to the fascination people had with him as an individual creator. He set the template for the artist who is at once master of technique and deep thinker – the brooding artist wrapped in contemplation of great projects (the popular image of Michelangelo often emphasizes his solitary, passionate nature, epitomized by him sculpting furiously or painting the Sistine ceiling alone on the scaffold).

In the field of sculpture specifically, later generations learned from Michelangelo’s technical innovations – his approach to carving, his willingness to attempt gigantic single-block statues, and his multi-figure compositions in marble. The scale of David influenced monuments for centuries. His integration of architecture and sculpture in the Medici Chapel presaged Baroque Gesamtkunstwerk ideas of unifying arts. Moreover, his expressive distortions of the figure (like the exaggerated muscles) opened the door for artists to move beyond naturalism when desired, paving the way to Mannerism and beyond.

Perhaps the ultimate legacy is that any subsequent sculptor of the human figure had to reckon with Michelangelo’s standard. From the muscles of David to the pathos of the Pietà to the titanic presence of Moses, Michelangelo’s works became part of the visual vocabulary of Western art. They have been copied, adapted, parodied, and revered in equal measure. To this day, young art students sketch his sculptures in museums to learn anatomy and form. His influence is literally carved into the stones of art history.

Conclusion

Michelangelo’s contributions to sculpture and art are monumental. He took the heritage of classical Greece and Renaissance Florence and elevated it to new heights, creating works of sublime beauty and spiritual power. As a sculptor, he combined flawless technique with a profound philosophical vision – treating marble as the medium through which hidden truth is revealed, “releasing the form within the stone”. His sculptures from the Pietà to David to Moses radiate a psychological depth and emotional intensity that was revolutionary for their time and remains deeply moving today. In each chisel mark, one sees an artist not only depicting the human form but almost breathing life into stone.

In art history, Michelangelo stands in a pantheon of one. He was admired as “the Divine Michelangelo” in his own era, and in the centuries since, his reputation has only grown. He is celebrated not just for individual masterpieces but for fundamentally expanding what sculpture could express. Before Michelangelo, no sculptor had infused stone figures with such a range of human experience – from the serene grief of the Pietà, to the confident vigilance of David, to the dreadful anger of Moses, to the tormented struggle of the Captives. His work encapsulates the Renaissance quest for perfection and the Mannerist/Baroque inclination toward drama and emotion. Little wonder that Michelangelo was often called “il migliore artista” – the greatest artist.

Michelangelo’s place in art history is secure as a giant who straddled multiple disciplines, but it is his sculpture, above all, that immortalized him. These marble beings he created seem to live on in our collective imagination. They have become icons of Western culture – instantly recognizable and endlessly inspiring. In the final analysis, Michelangelo not only sculpted figures of astounding beauty; he shaped the course of sculpture itself, leaving a legacy that gave form to the ideals of his age and continues to influence artists and captivate audiences over 500 years later. His genius, as solid and radiant as his carved marble, ensures that Michelangelo will forever be remembered as a master without equal in the realm of sculpture.